These two young men both died in the first half of 1915, at the age of 27; both had written poems which are now widely studied; both came from fairly privileged backgrounds. However, today almost everyone has heard of Rupert Brooke, while Julian Grenfell’s name is relatively unfamiliar to most, unless they are actually studying his poetry. In this feature article, we examine the background and legacies of these two extinguished stars.

Rupert Brooke’s name has become synonymous with the eager, handsome young Englishmen, who bravely volunteered to fight – and if necessary die – to protect their beloved country. Those who have heard of Julian Grenfell tend to think of him as having been somewhat warmongering and pugnacious, the spoiled son of Lord and Lady Desborough. Both descriptions are, to some extent, accurate but they also mask very different stories, demonstrating that these two men actually had a great deal in common.

THE EARLY YEARS

Rupert Chawner Brooke was born on 3rd August 1887 at Rugby, where his father, William, was a Classics master. He was the middle of the three sons of William and his wife Mary. Rupert’s older brother, Richard, (who died in 1907) was given the prophetic and patriotic middle name of ‘England’, while his younger brother was named William Alfred – both regal names. Rupert and Chawner were both names which were taken from his mother’s family – her grandfather having been named Rupert Chawner. Mary Brooke was a domineering woman, determined that her sons should do well, but equally intent on their happiness.

Rupert entered Rugby School in 1901 and was an immediate success, proving himself to be a hard-working and proficient student, as well as an excellent sportsman. This, coupled with his eye-catching mane of red-gold hair and classical good-looks, ensured his popularity.

In 1906, he won a scholarship to King’s College Cambridge where he had a thoroughly enjoyable time, boating on the Cam, having picnics and falling in love, which he did quite frequently. Needing, however, to focus on his degree, Brooke moved into The Old Vicarage at Grantchester, the atmosphere of which he would later capture in his most famous pre-war poem, of the same name. In 1910, Brooke’s father died suddenly, so he travelled back to Rugby and acted as temporary Housemaster for one term. This was followed by an unsuccessful love affair, the failure of which saw him leave the country to travel in France and Germany. He returned to London in December 1912, where he enlarged his circle of friends to include Arthur and Violet Asquith (children of the Prime Minister) and Edward Marsh, through whom he met Wilfrid Wilson Gibson and, later, Siegfried Sassoon.

In March 1913, following a nervous breakdown, Brooke left England again, this time travelling firstly to America and Canada, then New Zealand, before arriving in Tahiti, where he fell in love with a beautiful Samoan girl called Taatamata. He returned to England in June 1914 and when war was declared in August, Edward Marsh used his influence with Winston Churchill (who was then the First Lord of the Admiralty), to gain Brooke a commission in the Royal Naval Division.

Julian Henry Francis Grenfell was born on 30th March 1888 in London, although his family lived mainly at the Grenfell estate, Taplow Court in Buckinghamshire. He was the oldest child of William and Ethel Grenfell, who were both well known in their own circles. William was an MP, but was also a renowned sportsman and adventurer, who would later become chairman of the British Olympic Association and organiser of the 1908 London Olympics. Ethel, or Ettie, as she was universally known, was a society hostess, renowned for her beautiful and lavish parties. She also enjoyed a series of mild flirtations, which – as was the custom in those days – were tolerated by her husband. A second child, Gerald William (known as Billy) was born in March 1890, followed by a daughter Monica in 1893 and a third son, Ivo, in 1898. A second daughter, Alexandra (known as Imogen), completed the family in 1905.

Julian and Billy were close enough in age to soon become rivals and they fought quite often. Their education was initially begun at home, with a governess named Miss Poulson, then in 1898 Julian went away to Summerfields – a boarding school near Oxford, where he was joined two years later by Billy. Being away from home brought the two boys closer together and although they were both competitive, they argued much less. Julian was good at sports and art, while Billy was more academically gifted.

In 1901, Julian moved up to Eton, where he was a contemporary of Edward Horner (who would later become brother in law of the Prime Minister’s oldest son, Raymond), Ronald Knox (who later converted to Catholicism and became a noted author) and Patrick Shaw-Stewart (who would later become one of Ettie Grenfell’s admirers and then go on to serve with Rupert Brooke during the First World War). Again, Billy followed on and here, their competitive natures were even more apparent than before, enhanced by Ettie, who played one boy off against the other in her letters. It was at this stage that Julian first began to question his mother’s domineering role in his life and her constant need to involve him in her social activities, when he really preferred his own company, or that of just a few friends. In 1905, Willy Grenfell was raised to the peerage as 1st Baron Desborough.

In 1906, Julian went to Balliol College, Oxford, along with Horner, Knox and Shaw-Stewart. Here he tried to exert his independence, a task made somewhat easier by Ettie’s infatuation with her latest admirer, a man named Archie Gordon, who was only three years older than Julian.

In his last year at Oxford, Julian became frustrated by his mother and her social set to such an extent that he wrote a book in which he questioned the moral standards of English Society – in other words, he appeared to openly criticise his mother and her friends. This was not well received by his family, who ignored both him and his publication. Julian turned instead to love, in the form of Marjorie Manners (Lady Victoria Marjorie Manners), although his choice did not please Ettie who connived to place as many obstacles in their path as she could. This was, therefore, a very frustrating time for Julian, made worse by the death in a car crash, of Archie Gordon. All of this accumulated into a nervous breakdown, as a cure for which, Julian travelled to Italy to recover his health.

He returned to England in 1910 and had a brief affair with Pamela Lytton, to whom Ettie raised less objections, mainly because Pamela was married, which made this a ‘fling’ rather than a serious relationship. In any case, this liaison was cut short by Julian’s decision to join the army.

In the autumn of 1910, having completed his training, Julian embarked for India with the Royal Dragoons. This was an enjoyable time for him, as he spent his spare time riding, hunting and playing polo. Less favourable, however, was South Africa, where Julian was posted in late 1911. He began to contemplate leaving the army: he’d becoming interested in painting, but more seriously, he considered a career in politics.

THE WAR

When the First World War began in August 1914, most of the regular British Army who were stationed overseas, were recalled to England, including Julian’s regiment, who sailed from South Africa on 25th August, landing in England on 10th September. Billy, meanwhile had applied for a commission in the Rifle Brigade. Julian embarked for France on 6th October, where he went immediately to the Ypres Salient. There was little requirement for cavalry regiments, so Julian’s first taste of action, in the First Battle of Ypres, was with the infantry.

Julian Grenfell’s reputation as a ‘happy warrior’ stems from a letter which he wrote to his mother at this time, in which he said that he adored war and found it be ‘like a big picnic’. However, when read as a whole, the context of this statement is that he was enjoying the companionship and the freedom of fighting – such as the fact that no-one ever complained at him for being ‘dirty’, and the tone is reminiscent of the letters which he had written to his mother while he was at boarding school. At the same time, he also admitted that he found war ‘bloody’ and that the sight of refugees and wrecked villages was ‘miserable’ and ‘piteous’. Julian was certainly a most courageous officer – he was twice mentioned in dispatches and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in November 1914.

The following month, he was back in England on leave and returned to the front in January 1915, having been offered – and declined – a safe ‘staff’ job, working for General Pulteney – a friend of his mother’s.

The War Memorial, Taplow Court Gardens, in memory of Julian and Gerald ‘Billy’

Spring of 1915 saw a renewal of offensives and on 22nd April the Germans made the first use of poison gas. Julian’s diary entry for 29th April notes: ‘Wrote poem – Into Battle’. On May 13th Julian was wounded when a shell exploded near to him and a splinter of metal was lodged in his skull. He was taken to a Casualty Clearing Station, from where he wrote to Ettie, saying that he was doing ‘splendidly’. He was then transferred to a hospital at Boulogne, near to where his sister Monica was nursing. She visited Julian and was able to send a telegram to her parents to allay their fears. However, an X-ray on the 16th showed that his wound was much more serious than had originally been assumed, and that an operation was required. Monica sent another telegram, urging her parents to travel to Boulogne, if possible. They used their influence and arranged to travel on an ammunition boat, which arrived at 5am on 17th May. Three days later, Billy also paid his brother a visit – his battalion had just arrived in France and he had been granted permission to visit Julian. His family kept a vigil at his bedside until May 26th, when Julian died. On the day that news of his death appeared in The Times, it was accompanied by the first ever publication of his poem, Into Battle.

Billy Grenfell was killed leading his men in a charge on 30th July 1915, less than one mile from where Julian had received his wound. His body was never found and he is listed among the missing on the memorial at the Menin Gate. Ivo, the third and only surviving son, was killed in a car accident in 1926, and thus the Desborough line died out, affording Willy the dubious honour of being ‘First and Last Baron Desborough’.

Rupert Brooke’s war was very different from that of Julian Grenfell. Sub-Lieutenant Brooke sailed for Antwerp on 4th October 1915. He was serving in a battalion named Anson (the Royal Naval Division named, rather than numbered, their battalions) and they were supposed to help stop the German army’s advance through Belgium. By the time they arrived, however, it was clear that this exercise had already failed, so Brooke found himself joining the Belgian refugees, who were fleeing the advancing German troops. By October 9th, he and his battalion were back in England.

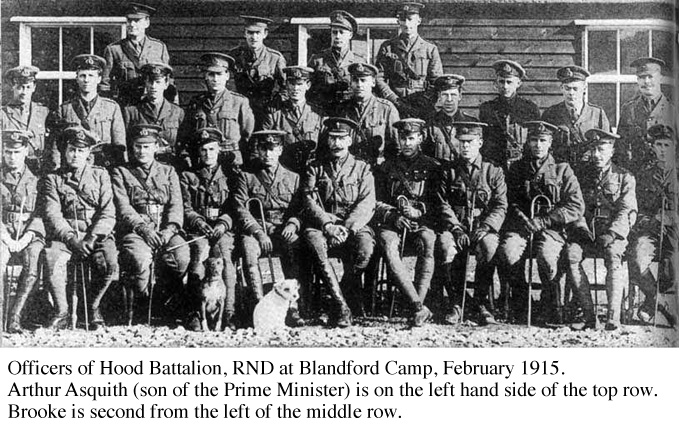

In November, Brooke was transferred from Anson to Hood Battalion and was moved to Blandford Camp in Dorset, together with Arthur Asquith and Patrick Shaw-Stewart, who at that time was maintaining a regular and loving correspondence with Ettie Grenfell. It was around this time that Brooke started to write his 1914 Sonnets, which he completed in early 1915 and sent to his friend Wilfrid Wilson Gibson.

In early February, Brooke became ill and was nursed back to health at 10 Downing Street by Violet Asquith. Once fully recovered, he rejoined his battalion and in late February, set sail on the Grantully Castle, bound for Gallipoli. There were several stops during the journey, which afforded Brooke the opportunity to dine in Malta, enjoy a performance of Tosca and visit the Pyramids and the Sphynx.

At the beginning of April, while still on board the Grantully Castle, anchored at Skyros, Brooke complained of feeling unwell and had also developed a sore on his upper lip. He seemed to improve and received a letter from Edward Marsh, telling him that his sonnet The Soldier had been read out during a service at St Paul’s Cathedral.

On April 20th, the sore on Brooke’s lip was worse, he was once again unwell and had a very high temperature. By the following day his condition had deteriorated further and was now drifting in and out of consciousness. Medical officers and surgeons attributed his illness to an infected mosquito bite and despite their attempts to save him he died on the afternoon of 23rd April (appropriately, St George’s Day). He was buried in a hastily arranged funeral service, in an olive grove on the island of Skyros in the company of his friends including Patrick Shaw-Stewart and Arthur Asquith.

Brooke’s 1914 Sonnets sold in their thousands and ran to many, many editions, giving a secure financial future to his literary legatees, who included Wilfrid Wilson Gibson. In common with the Grenfells, there would be another blow to Brooke’s mother, Mary, when Rupert’s younger brother William, a Second Lieutenant in the London Regiment, was killed in action on 14th June 1915. As her eldest son Richard had already died in 1907, and her husband in 1910, Mary Brooke was now alone.

THE LEGACY

By the middle of 1915, both the Grenfells and Mary Brooke had suffered the tragic losses of two of their sons. Julian Grenfell was mourned by all who knew him as a ‘joyous’, ‘brave’ and ‘noble’ young man, of whom Winston Churchill privately wrote: ‘He was all… that our race needs to keep its honour fair and bright…’. Rupert Brooke was canonised, given the status of a Demi-God by many who wrote about him and Winston Churchill said of him, publicly in The Times, that ‘… he was all that one would wish England’s noblest sons to be…’. Given that their backgrounds were quite similar and their deaths so widely, greatly and similarly acknowledged, why are the perceptions of these two men so different today – both from each other and from the other soldier-poets who would follow in the later years of the war?

If one says to a group of people the words ‘If I should die, think only this of me…’, almost everyone will have heard them spoken, many may be able to recite the next line and some will know who wrote them. However, if one says ‘The naked earth is warm with Spring…’ people are likely to look quizzical and shrug their shoulders, unaware that this is the first line from Julian Grenfell’s Into Battle. Even when informed of this fact, they are wont to reply ‘Julian Who?’.

Much of this inequality in the legacies of these two poets stems from the immediate aftermath of their deaths. When Brooke died, his friends were quick and eager to bring his work to the public eye. His type of patriotic poetry was very popular at the time and this, coupled with the fact that Brooke had died on St George’s Day and his stunning good-looks, made the creation of a myth quite an easy task. Brooke suddenly achieved the status of a brave, almost God-like creature who had died defending and preserving the honour of his beloved England.

Grenfell’s immediate legacy, on the other hand, was entirely controlled and moulded by his mother, Ettie, who wrote a Family Journal in memory of Julian and Billy. In this, she ‘doctored’ letters and even made minor amendments to Julian’s poem Into Battle (none of which were improvements). To Ettie, Julian was primarily a soldier, not a poet. The army was the profession into which she had always intended he should go, so to her, he was really a soldier who wrote a few verses and painted a bit.

That said, in the eyes of both the critics of the day and the public, both men were thought of as heroes and their poetry was, generally speaking admired. T. Sturge Moore, in his 1920 appraisal of war poets entitled Some Soldier Poets, comments that Grenfell and Brooke stand together, and that he sees them ‘through their work, in attitudes that suggest statues more worthy of the acropolis of the supreme city than any of those which the public figures of these times have yet assumed.’ He goes on: ‘The ardent Grenfell leaps forward; Brooke with smiling grace escapes from the uncomfortable admiration of a bygone age – both bent on grasping by the hand their new best friend, Death.’ The only real difference between the two men would be that Brooke’s friends advanced and perpetuated his poetic legacy, while Ettie looked upon Julian’s as only a small part of the soldier who had once been her son.

Today, many students will research Brooke’s poems and compare them with those written much later in the conflict by Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon or Isaac Rosenberg: few will carry out the same task with Grenfell’s Into Battle. Perhaps this is because Brooke, with his God-like mythical status, still captures the imagination, while Grenfell’s less appealing upper-class professional soldier background holds less attraction. Brooke, for most people, typifies the young, loyal Englishmen who willingly answered his country’s call; Grenfell does not.

Others might argue that Brooke’s poetry is more appreciated today, simply because it is better than Grenfell’s. Well, Brookes’ sonnets are certainly shorter, but they are by no means superior and indeed they show signs of being quite repetitive. Brooke, it could also be said, is a little obsessed with sentiment and self-sacrifice – an argument first propounded in 1915 by Charles Hamilton Sorley. One could equally claim that in Into Battle Grenfell focuses too much on the glories of death in battle – seen by him as an ‘increase’ – and that the poem becomes a little lost and confused, which is not surprising, given that the original manuscript contains many changes, including some which Grenfell made to the order in which the verses should appear. The works of both poets contain flaws; they also contain moments of utter genius and beauty – a hint perhaps of what might have been.

Since their deaths, these two men have been eclipsed – to different degrees – by the over-idolised and seriously over-studied, Wilfred Owen, who appears at times to be the only war poet that many examining boards have ever heard of, and by the fact that their poetry and its subject declined in popularity as the decades passed. The myth of ‘lions led by donkeys’ which became popular in the 1960s meant that people did not want to believe that men had gone willingly to their deaths, but preferred to read the irony and bitter cynicism of poems by Owen and Sassoon, or the sad recollections of Blunden, even if for no better reason than that it fitted in with their image of the war. However, both Grenfell and Brooke, and their stories have a great deal to offer those who are studying, or take a genuine interest in this topic and neither they nor their poetry should be derided, simply because its content does not fit in with commonly-held misconceptions about the conflict. These two men offer us a glimpse of a forgotten time, when glory, honour and duty still mattered. Reading their biographies, one can see that they had a lot in common; not least of which was their acknowledgement that to fight in the Great War was their responsibility – even, one might say, their privilege, or their right. More importantly though, one can also see their dissatisfaction with their own pre-war lives and almost sense their relief that the war (as they perceived it) finally offered them a means of escape from the banality. They also show us that, for them at least, their generation was, to a certain extent, already ‘lost’, long before the carnage of the battlefields afforded them that hard-earned title.

Great Hall, Taplow Court

Taplow Court

Taplow Court

Rugby School

Rugby School, c.1815

King’s College, Cambridge

Balliol College, Oxford

The Old Vicarage, Granchester

The Old Vicarage, Granchester

Lord Desborough

“Willie and Ettie”

Ivo, Monica and William

Ettie Grenfell

Ettie Grenfell with Julian and Billy (i)

Ettie Grenfell with Julian and Billy (ii)

Grandly Castle off Salonikang

Grantully Castle

The Rupert Brooke statue

Rupert Brooke’s gave on Skyros

Birch Green War Memorial